A different kind of cultural revolution — Warwick Brown

A major exhibition of his paintings in the China National Museum and a tour

of his work throughout China are a dream come true for New Zealand artist

Sean Chen. Warwick Brown was there.

“Brown, I want you to come to Beijing and open my exhibition.” That was the opening sentence of the phone call I answered in February this year from Sean Chen, an Auckland-based artist whose career I had initially taken an interest in around 15 years ago. The conversation then became more curious. This was no small show in a backstreet dealer gallery, but a substantial exhibition of 44 paintings by Chen to be held in the China National Museum in Tiananmen Square, from 9 – 22 April this year.

His story started in Hangzhou City, China, where his parents were teachers, and several relatives were artists. In 1967, at the age of nine, his education was rudely interrupted by the Cultural Revolution. The regime started burning books, so his parents hid their extensive library in the servants’ quarters in the grounds of their large home. The family were later evicted into the cramped servants’ quarters, and their home was occupied by several poor families. Chen’s family was labelled as bourgeois, he was too young to join the Red Guards, and was unable to attend school, so he spent his growing years in the little house full of books. Over the next few years he read them all and recalls that this period opened his mind to many things.

Chen then studied art at night classes, and in the late 1970s worked as a professional artist for the Zhejiang Province’s television studios and the Art and Culture Institutes of Hangzhou City, where he developed his painting skills further. In 1984 – 85 he participated in exhibitions of social realist art and in 1986 became a member of the Artists Association of China. Chen emigrated to Australia in 1986 and then to New Zealand in 1988. Realising there was no signwriting firm in Auckland catering to its large Chinese community, he set one up, and it quickly prospered. His most well known work was a massive soya sauce advertisement painted on a Fanshawe Street warehouse wall, consisting of 19 nine-metre high sauce bottles, stretching 100 metres along the street. In a 1997 article bemoaning the lack of public art in Auckland, Herald columnist Tessa Laird gave the bottles her personal public art award, saying: “This monstrous edifice, which looks as though it were dreamed up by a Chinese Andy Warhol, makes heading to the North Shore almost worthwhile”.

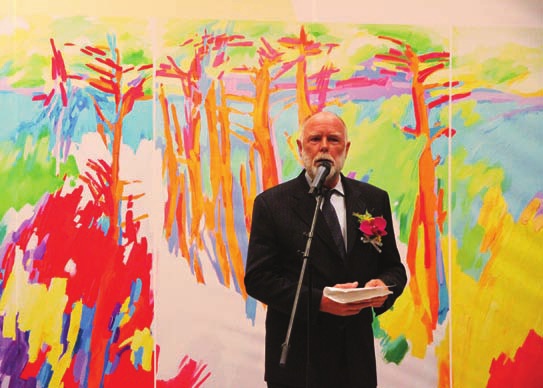

Sean Chen speaking at the opening of his exhibition at China National Museum

statues of former revolutionary leaders in the foyer of China National Museum

Sean Chen, Tai Poutini National Park South Island, 2011, oil on canvas, 145 x 200 x 145cm

Supported by his business Chen travelled widely, further broadening his knowledge of art, visiting galleries overseas and absorbing new influences. On his return to Auckland he began sketching and painting. His by now iconic sauce bottles had earned him the reputation of a ‘landmark artist’, so he decided to repay the city that had been so good to him by painting its landmarks. He became a member of the Auckland Society of Arts in 1992, and displayed his work in their members’exhibitions.

By 1998 Chen felt confident enough to seek out a commercial dealer to exhibit his work. He approached Portfolio Gallery in Lorne Street, Auckland, where I happened to be the director. I immediately discerned that Chen was not one of those artists who have undoubted painting skills but no originality or imagination – the ‘junk painters’ I call them. I was struck by how un-Asian Chen’s work appeared; on the contrary, it looked more like the work of a European who had thoroughly assimilated modernism. But that was not the only surprise. Instead of warmed-over European subject matter Chen was painting Auckland, and instead of doing so in a clichéd fashion, he was doing it with wit and imagination. His chosen subjects, well known Auckland landmarks, could have been tedious and predictable, but they were not. Buildings were wonky, perspectives were skewed, colours were odd, compositions were unusual. Instead of his work coming across as what I would describe as illustrative ‘telephone-book-cover’ art, Chen’s paintings were tough enough to avoid that annoying, childlike look achieved, perhaps unconsciously, by many representational artists who think they’re being adventuresome and modern. I decided his work was interesting and well worth exhibiting.

The rest, as they say, is history. After two sell-out exhibitions at Portfolio Gallery in 1999 and a third at the Peters Muir Petford Gallery in 2000, Chen exhibited annually at Flagstaff Gallery between 2002 and 2005. The word spread and Chen now sells privately all the work he can produce.

I’d never been to mainland China, so quickly accepted Chen’s invitation, and two months later found myself in central Beijing, being whisked around the city in a chauffeured Mercedes. Tiananmen Square is approached from a very long, straight, wide road (ideal for parades and massed tank manoeuvres) that dates back to imperial times. It was once part of the approaches to the Forbidden City, and one of the former gatehouses now serves as Mao’s tomb. While I was there half the square was off limits and patrolled by soldiers in immaculate uniforms. There were also large numbers of plainclothes police lurking about. They make no attempt to be ‘invisible’ – on the contrary, at knock-off time they form up behind a squad of marching soldiers, no doubt to remind the populace that they exist. Impassive soldiers stand to attention at odd places in ones and twos, and the streetlight poles are festooned with observation cameras. For a foreigner the atmosphere is quite intimidating, although the locals don’t seem to mind.

Warwick Brown at Chen’s exhibition opening

Prime Minister John Key with Sean Chen

On the north side of the square is the familiar templelike building draped with red flags and with Mao’s portrait in the centre, from which speeches were made during the revolutionary period. On the west side stands the Great Hall of the People, and on the east the huge National Museum, China’s equivalent of our Te Papa, only many times larger. The entrance lobby is the full four-storey height and width of the building, with a marble floor, and it contains statues of the leaders of the revolution. Elsewhere can be found many of the surviving art treasures of ancient China: painted scrolls, watercolour and ink landscapes, bronze bells, carved jade and so on. Part of the ground floor houses all the most precious socialist realist paintings from the Mao period. They’re hung in a red-painted gallery so large that, when you stand on one side and look at the paintings on the opposite wall, they look like postage stamps. They all feature smiling peasants and workers listening to Mao speak, or fearless fighters raising their rifles against the enemies of the people.

Chen’s show received equal billing in the vast lobby with a show of masterpieces on loan from the Metropolitan Museum in New York, including works by Turner, Rembrandt, Van Gogh and Monet. This was the first appearance of a New Zealand artist at the China National Museum, and the show came about because of two recent developments. Firstly, the new director has embarked on a policy of opening up the museum to modern art, although I suspect it will be quite a while before biennale type conceptual, political and installation art will be seen there. Secondly, for several years the Overseas Chinese Affairs Office in Beijing has been bringing back the work of expatriate Chinese artists – from America, Canada and elsewhere. Chen’s approach to both these institutions was well-timed to coincide with increasing trade between New Zealand and China. His work still had to pass their quality standards, and he had to make a contribution towards the substantial exhibition costs.

The show, titled Pure New Zealand: Colourful World in the Eyes of Sean Chen, was in a large gallery space on the third floor. At the opening there was a large crowd of press and guests, everyone wore a spray of flowers, catalogues in special bags were handed out, and speeches were made in Chinese (including one by me via an interpreter). Everyone then trooped in to see the colourful collection of 44 paintings, mostly of New Zealand subjects, the largest of which was 18 metres wide. The show looked sensational in the large space, and the bright colour and expressive brushwork was an eye-opener to many of the Chinese visitors. New Zealand Prime Minister John Key, in town for a trade meeting with top officials, visited the show the next day.

Sean Chen, Otago Harbour, 2010, oil on canvas, 100 x 100cm

After two weeks in the China National Museum, the exhibition will tour to 27 municipal galleries in major cities throughout China for the next four years. Then the paintings will return to Beijing, where they will be auctioned and the proceeds donated to the China Environmental Protection Foundation. By that time Chen will be the best known New Zealand artist in China. Judging by the interest already shown in his work in China, it seems the auction proceeds may reach millions of dollars.